Jennifer A. Nielsen stated, ‘How do you destroy a nation? You take away their culture. And how is that done? You take their language, their history, their very identity. How would you do that?’ You ban their books.’

India’s 2023 criminal code declared 25 books ‘forfeit’, banning their circulation in the Himalayan region. The government of India has claimed that these books promote youth radicalization, ‘culture of victimhood’, false narratives, and secessionism. It is a deliberate and systematic strategy to silence Kashmiri voices and prevent them from raising their voices against injustice.

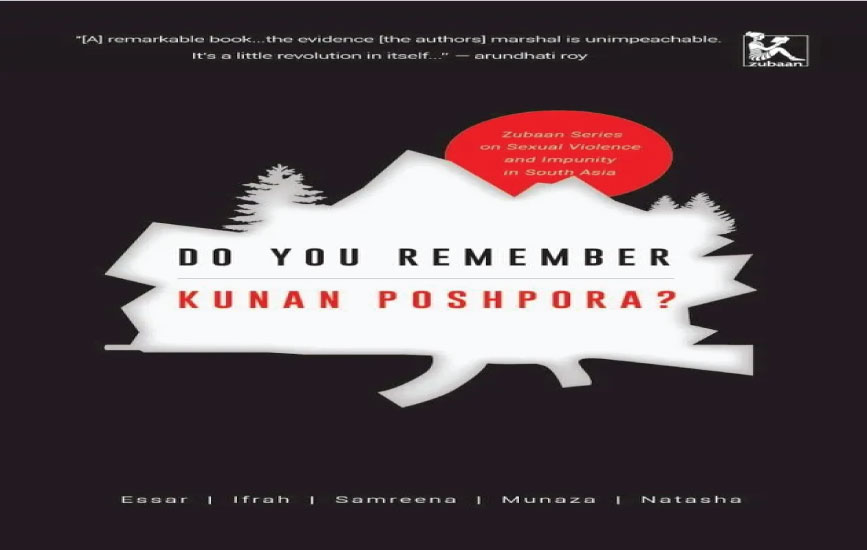

Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora, recounts a horrific night in the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora, located in the district of Kupwara, Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir, bordering Azad Kashmir. The book revisits the night of February 23-24, 1991, when Indian Security Forces, particularly the 4th Rajputana Rifles, entered the village and subjected local Kashmiri women to mass rape. The women were raped in the presence of their family members. The men were also tortured in the icy cold night outside the homes, without shoes, and their bodies had frozen.

According to the victim women, rape is not an adequate word to describe what was done to them. It was not rape, it was war. Women were caught and held by a minimum of five to six army drunk forces. (p. 88)

The book is structured into seven chapters, highlighting the plight of Kashmiri women, their roles in Kashmir’s resistance, and analyzing the political context. It also investigates documents, including police case diaries and Human Rights Commission records, and conducts firsthand interviews. The authors critically assess the narratives of the Indian government, which Research Officer, Center for International Strategic Studies (CISS), Muzaffarabad, Azad Jamuu and Kashmir (AJK), Pakistan. 35 Policy Perspectives 22:2 (2025) dismissed the testimony and documentation submitted by eyewitnesses and villagers, and reconstruct the incident through survivor verification and document efforts aimed at achieving justice.

The authors have quoted many brave Kashmiri women, like Asiya Gillani, Anjuman Zamurda Habib, and Parveena Ahangar, who lost her 14year-old son to enforced disappearance in 1990 and founded the Association of Parents of the Disappeared Persons to fight for justice. In this book, the women of Kunan Poshpora, who have been speaking the same language of resistance for 25 years, share a story that highlights the resilience and strength of women in the valley.

The literature highlights the shift of Kashmiri women from victims to survivors, who wield a stone and proudly challenge the Indian military on the streets, and their active engagement in the resistance movement.

They have chosen to resist in a variety of ways, including throwing a simple curse or a ‘Kangri’ (a fire pot) at occupied forces attempting to humiliate them, participating in stone throwing, participating in street protests and mass funerals, supporting the freedom struggle, and organizing and working in civil society to express political opinions and affiliations.

The authors express that the plight of Kashmiri women has suffered numerous losses, including killings, loved ones’ disappearances, and rape. Rape is used as a weapon of war and terror, with the case of Kunan Poshpora exemplifying the utterly horrifying forms of sexual violence committed against women in Kashmir by the Indian Armed Forces. These forces are using Kashmiri women as war trophies (p. 27). Sexual violence has been used not only against women but also as a weapon of power and torture against men in Kashmir. This violence is a tool of oppression, terrorizing communities and challenging state denials and institutional failures, transforming trauma into resistance and highlighting systemic justice denial.

The book also explores memory politics and collective forgetting, highlighting its importance as a tool for resistance and preserving counterhistories. Historically, it gives a rare archive of evidence, documents, and lived experiences of mass sexual violence by occupied forces, challenging silence and impunity. 36 Pages that Frighten Power: The Banned Literature of Kashmir The literature serves as a political act of defiance, advocating for justice and challenging institutional apathy. The book highlights the cultural significance of Kashmiri women’s voices, presenting their memories and resilience as vital to regional identity and collective justice.

The book also raises the question of whether rape in India is punishable but justifiable in Kashmir, where men in uniform protect India’s honor. It questions the Indian authorities’ tendency to deny justice and bury the truth for Kashmiris.