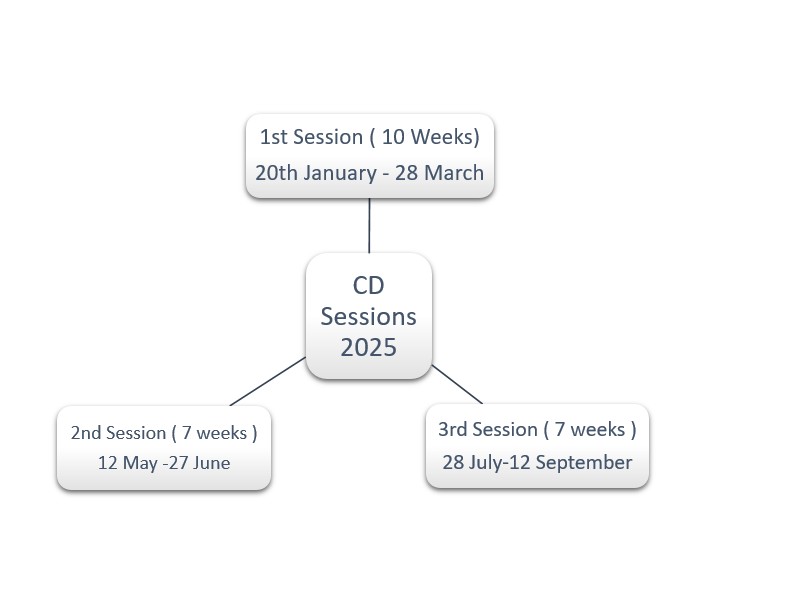

The Conference on Disarmament (CD) member states have convened for the 2025 plenary sessions, which will continue throughout the year. The first public plenary session began on January 20, 2025, and will run until March 28 at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. The second session is scheduled from May 12 to June 27, while the third and final session will take place from July 28 to September 12. Since its establishment in 1979, the CD has served as the primary forum for multilateral disarmament negotiations. The presidency of the CD rotates among its 65 member states on a monthly basis. In 2025, Italy held the presidency from January 20 to February 14, marking its first time in this role in eleven years. Japan assumed the presidency from February 17 to March 14, followed by Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malaysia, and Mexico in subsequent months. Each presidency lasts for four working weeks.

| Presidency of CD for four working Groups: 2025 Schedule | |

| Country | Date of Presidency |

| Italy | 20 January -14th February |

| Japan | 17th February 14th March |

| Kazakhstan | 17th – 28th March- 23 May |

| Kenya | 26th May to 20th June |

| Malaysia | 23rd-27th June to 28th July -15August |

| Mexico | 18th August 12 September |

The 2025 Conference on Disarmament (CD) is taking place at a difficult time. Ongoing wars in Europe and the Middle East have changed global politics, making major powers more suspicious of each other and increasing interest in nuclear weapons. With arms control and disarmament already weakening, this year’s CD meetings will be important for moving its core agenda forward and bringing all 65 member states together for dialogue and negotiation. The main negotiating body for multilateral disarmament agreements i.e. CD has suffered deadlock due to the diverging interest of its member states on CD’s Core agenda and the ability of actors to veto each other’s initiatives. Over 30 years, CD has focused on Decalogue and Core Agenda but it has failed to reach a consensus on the programme of work.

The last agreement to emerge from the Conference on Disarmament (CD) was the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). The end of the Cold War created an opportunity for the treaty, which bans all nuclear testing for both civilian and military purposes. However, the CD has since struggled to reach consensus on its core agenda, largely due to differences among member states that prioritize national interests over the benefits of compromise. This has weakened the CD’s ability to make progress.

The CTBT was the CD’s most significant achievement, but even its adoption required diplomatic efforts to bypass a deadlock. India refused to support the final version, forcing the treaty to be sent directly to the UN General Assembly for approval. Despite its historic significance, the CTBT remains unenforceable 25 years later because eight key states, including the United States and China, have not signed or ratified it. As a result, critical parts of the treaty, such as its Executive Council and on-site inspection mechanisms, remain nonfunctional.

The 2024 sessions of the Conference on Disarmament (CD) took place from January to September, with India presiding over the first plenary meeting in January, where the conference set its agenda for the year. Pakistan spoke at this opening session and commenced discussions on adopting the agenda. As part of its contributions, Pakistan submitted a working paper titled “Addressing the Security and Stability Implications of Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy in Weapon Systems.” This was done in response to Rule 27 and focused on the security risks linked to autonomous weapon systems and the use of AI in military operations. Pakistan accentuated the need to include this issue in the agenda, arguing that all states share a responsibility to adapt to the evolving security landscape.

Pakistan reiterated its position that the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT) focuses only on halting the production of new fissile material while ignoring existing stockpiles, which could undermine the security interests of many states. According to Pakistan’s official stance, international non-proliferation and disarmament efforts cannot be pursued in isolation from legitimate security concerns and national interests. Pakistan argues that the global non-proliferation framework must be rule-based, non-discriminatory, and equally responsive to the security needs of all states rather than catering to the interests of a selected few. On February 26, 2024, UN Secretary-General António Guterres commented on the “complete impasse” at the CD, stating that the Conference “needs to be reformed – urgently” to effectively advance multilateral solutions.

Despite ongoing challenges, the CD saw some progress in 2024 with the establishment of five subsidiary groups after prolonged negotiations. These groups were intended to provide a foundation for future discussions. However, since the agreement was reached at the end of the session, the groups were unable to convene. It is expected that key participants will reaffirm last year’s agreement. If the subsidiary bodies are re-established, they will address major issues on the CD agenda, including nuclear disarmament, war prevention, a potential treaty to ban the production of fissile material, security assurances for non-nuclear-weapon states, and the prevention of an arms race in outer space.

With Italy’s four-week presidency concluded and Japan now leading the meetings, attention is turning to how discussions on the CD’s core agenda will progress in 2025. Under Italy’s leadership, after extensive negotiations, the work program for 2025 was approved. The decision, adopted by consensus, established five subsidiary bodies to address key issues, including halting the nuclear arms race and preventing nuclear conflict, providing assurances to non-nuclear states against the use of such weapons, and ensuring security in outer space. Ambassador Bencini emphasized that “the CD does not operate in a vacuum” and acknowledged that current global tensions inevitably influence its work. However, he also pointed to opportunities for dialogue, stressing the need to resume negotiations on these critical issues.

The Conference on Disarmament (CD) has been unable to advance its core agenda of achieving a nuclear-weapon-free world, its original mandate, due to opposition from the five recognized nuclear-weapon states (P5). For meaningful progress, nuclear disarmament must be universal, non-discriminatory, and verifiable, ensuring equal and undiminished security for all.

The second major agenda item, the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT), remains deadlocked. The proposed treaty focuses solely on halting future production of fissile material, overlooking the extensive stockpiles already held by P5 states, which have since ceased production. Pakistan has called for a more inclusive, non-discriminatory approach that would extend the treaty’s scope to cover past stockpiles as well. The Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) has been on the CD’s agenda since 1968, aiming to ensure that space remains free of weapons. However, discussions have stalled due to U.S. opposition, which suggests an interest in militarizing space rather than supporting an agreement to prevent its weaponization.

Another key agenda item, addressed under Subsidiary Body 4, is Negative Security Assurances (NSAs), a commitment by nuclear-armed states not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states. Since 1979, efforts to establish a legally binding multilateral treaty on NSAs have failed. While such a treaty could strengthen security assurances and curb the spread of nuclear weapons technology, opposition from the U.S., U.K., Russia, and France has left this issue at a stalemate.

The work of the 2025 subsidiary bodies will continue until September, when a report will either be approved in the plenary session or, as in 2024, face a complete deadlock. The primary responsibility for progress rests with the five recognized nuclear-weapon states (P5), which are legally obligated under Article 6 of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to pursue nuclear disarmament.

However, meaningful arms control and disarmament can only advance if they follow a non-discriminatory approach and if states are willing to make compromises. The current global environment suggests otherwise, as many states appear more focused on developing and modernizing their nuclear arsenals rather than engaging in genuine disarmament efforts.

Authors

Tayyaba Khurshid, Research Officer at Center for International Strategic Studies AJK

Nazia Sheikh, Research Officer at Center for International Strategic Studies AJK